Tue 15 Jun 2010

Doc-U-Rama

Posted by Ethan under Film Review, NYC Film Critic

1 Comment

Reviews of three documentaries now in theaters.

Stonewall Uprising

Directed by Kate Davis and David Heilbroner

Written by David Helbroner

***1/2

Despite the Herculean strides the gay rights movement has made over the past forty years, recent events like California’s battle over Proposition 8, John McCain’s stubborn opposition to repealing the military’s biased “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell†policy and Ramin Setoodeh’s boneheaded Newsweek article questioning Sean Hayes’ ability to play a straight man indicate that there’s still a lot of work to be done before full equality is reached. Nevertheless, the fact that these debates are playing out so publicly—and that the voices in favor of gay rights are at last starting to drown out the voices of those opposed—shows just how significantly the landscape for gays and lesbians has changed since the early 1960s, which is where the new documentary Stonewall Uprising begins its story.

The portrait directors Kate Davis and David Heilbroner paint of that era is damning; firmly forced into the closet by a mainstream society that hated and feared them, gay men and women sought refuge in underground bars and clubs, as well as the privacy of their own (or someone else’s) homes. (At least, that was the case for those lucky enough to live in a big city like New York; gays in small towns rarely had any place to gather.) The small number that had the courage to out themselves often struggled for public acceptance. Among the movie’s wealth of archival material is an eye-opening television interview with one of the heads the Mattachine Society, an early gay-rights organization, in which he not only states that his group doesn’t support gay marriage, but also that he himself gave up being gay several years ago because “it wasn’t my cup of tea.”

Not surprisingly, these half-hearted efforts didn’t do a lot to change the national opinion. Gays were regularly vilified in the public sphere, denounced by law enforcement types, portrayed as dangerous lunatics in the news media (even respected newsman Mike Wallace was anything but “fair and balanced†when profiling the community in a cringe-inducing 1967 CBS News special) and diagnosed as mentally ill by the medical establishment. One particularly disturbing sequence in the film deals with the forced institutionalization of some of the men and women who were said to be suffering from homosexuality; locked away in asylums, they were forced to undergo electroshock therapy and, in some cases, lobotomies as doctors searched for a “cure.” That these practices were condoned and even supported by professional medical experts is truly frightening. More than anything, it further exposes the lie often perpetrated by the fringe right arguing that the country was better off fifty years ago with the “way things used to be.”

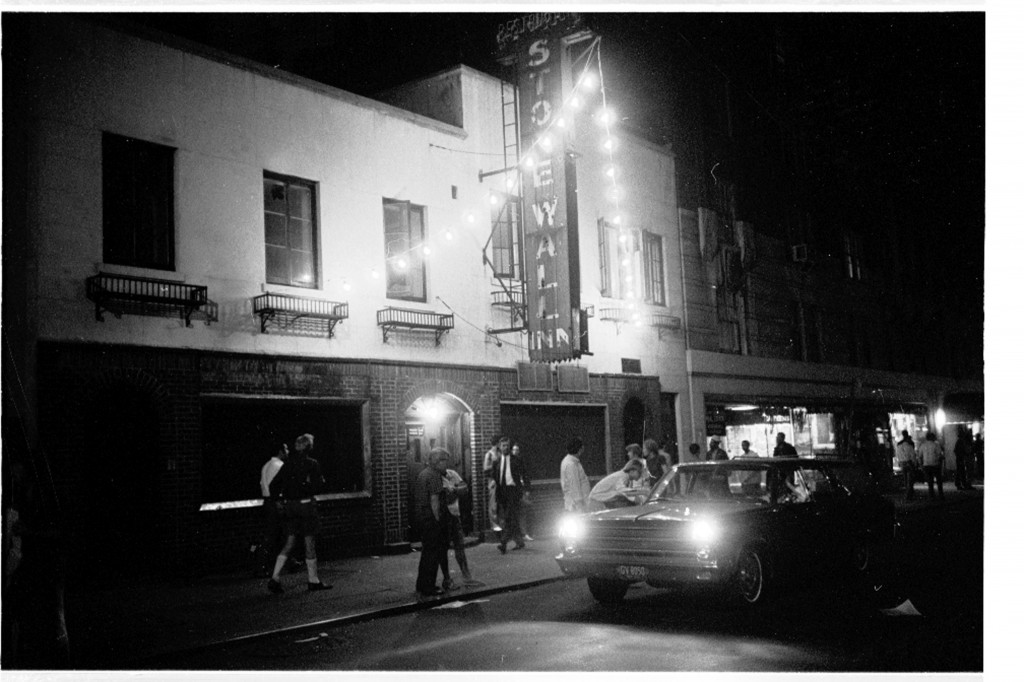

But Stonewall Uprising isn’t simply a chronicle of the bad old days. As the title implies, the bulk of the movie deals with the extraordinary events that occurred on the night of June 28, 1969 at one of New York City’s most popular gay bars, The Stonewall Inn. That evening, the NYPD launched one of their typical raids, only to be pushed back by the mad-as-hell-and-not-going-to-take-it-anymore clientele. Eventually, the cops had to barricade themselves inside the Stonewall, while a small army of gays and lesbians protested in the street for almost three days. That uprising launched the modern gay-rights movement, beginning with the now-annual Gay Pride march the following year. It’s a great story, one that’s told here through the words of some of the people who were there that night, including several protestors, two journalists and the police inspector in charge of the raid.

Because little footage of the Stonewall riots exists, this is the one section of the film where Davis and Heilbroner rely almost entirely on dramatic recreations. It’s an understandable decision, but ultimately an unnecessary one as the subjects’ words evoke the Stonewall riots quite vividly without the aid of visual references. It’s also a shame that the directors weren’t able to find a slightly more diverse group of talking heads. With the exception of two women, everyone interviewed here is male and, more significantly, white, even though archival photos reveal that the Stonewall’s patrons came from all walks of life. (Indeed, it would have been fascinating in general to hear how a black gay man’s experiences in the 1960s paralleled or differed from a white man’s.) Overall though, Stonewall Uprising is an insightful and moving documentary, one that makes you prouder of America’s present and more hopeful for its future.

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

45365

Directed by Turner Ross and Bill Ross

***

Back in the silent cinema era, there was a type of movie known as the city symphony, a plotless portrait of a famous metropolis scored to a soaring soundtrack. New York, Berlin and Moscow were some of bustling locales given the city symphony treatment and those films remain invaluable windows into a time and place that’s lost to us now. Bill and Turner Ross’ 45365 is a contemporary version of a city symphony, albeit one that differs in a number of formal and stylistic ways from its predecessors. The title is the zip code of Sidney, Ohio, a town of about 20,000 residents located in the center of the Buckeye State. Not coincidentally, Sidney is also the brothers’ hometown, which they returned to after many years in L.A. to shoot this film over the course of roughly a year. Their roots in the community probably explain why their camera is allowed to roam so freely; in addition to filming everyday citizens, they also follow a cop on his nightly beat, a radio disc jockey through his shift in the studios of WMVR—Sidney’s Variety Station!—and the Sidney High School Yellow Jackets football team from the locker room to the field.

Like the city symphonies of old, 45365 doesn’t have a traditional three-act plot, but it does employ a more linear structure, beginning in the early summer and drawing to a close as winter descends on Sidney. The Ross’ also return to select faces throughout, checking in on their personal narratives. For example, there’s a local judge who hits the campaign trail to ensure his re-election, a women wrestling with a number of personal and professional challenges (a bad boyfriend appears to be in the picture) and another woman with a teenage son who often gets into trouble and actually winds up in a courtroom towards the end of the film. (Obviously, the presence of “dialogue†is another big difference between 45365 and the silent city symphonies of the 1920s.) Neither of these stories takes center stage in the film, which moves at its own distinct rhythm, cutting between scenes based on an action and/or a location rather than for purely narrative reasons. The overall effect is almost hypnotic, as this town and the people in it drift in and out of focus for some 90 minutes.

In many ways, 45365 functions as an interesting complement and counterpoint to another modern city symphony I saw earlier this year, Zhao Dayong’s Ghost Town, about a remote village in China that is slowly falling to ruins as young people move away and the elderly die off. 45365’s depiction of Sidney is far less grim—indeed whatever larger economic and social pressures that may have existed in the state while the Ross’ were shooting don’t make their way into the film. (One man’s discussion of why he believes in voting independently rather than aligning with an established political party is the closest the movie gets to exploring the town’s politics.) To a certain extent, that lack of a larger context does hamper the film. Sidney emerges here neither as some kind of urban wonderland like a ‘20s-era Berlin nor as a neglected relic like Dayong’s ghost town. It’s an average mid-sized city where people go to work and school and, in general, take things one day at a time. The sheer ordinariness of life there makes it somewhat difficult to understand the filmmakers’ fascination with the place, apart from, perhaps, childhood nostalgia or as an extreme contrast to the city that they’ve since adopted as their home. Then again, that ordinariness seems to be the point of the film. Where previous city symphonies functioned primarily as celebrations of technology and engineering—look at the wonderful things we can build!—this one is ultimately about the city as community, focusing on the small, everyday connections formed between people living in a shared space.

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work

Directed by Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg

***

I’d been hearing good things about this fly-on-the-wall portrait of comedienne/fashion critic/all-around misanthrope Joan Rivers since it premiered to general acclaim at the Sundance Film Festival in January. It’s nice to report that the film mostly lives up to the hype. Smartly assembled by directors Ricki Stern and Annie Sundberg, A Piece of Work places Rivers’ groundbreaking four-decade career in context for those contemporary viewers who primarily know her as a punching bag for plastic surgery jokes or as a staple on awards show red carpets.

But the filmmakers don’t spend too much time dwelling on the past; instead the bulk of the movie spans a very eventful year in the now 75-year-old performer’s life, beginning with her attempts to launch a one-woman show in the U.K. with tentative plans to then open it in on Broadway (plans that are later scuttled when the reviews are weaker than she would like) and ends with her winning the NBC reality series Celebrity Apprentice. A savvy businesswoman–she refers to herself as “a brand†without a trace of irony–Rivers clearly views this film as another way to publicize her career and presents herself as a workaholic who will perform anytime, anywhere particularly if the price is right.

Fortunately, Stern and Sundberg do manage to capture several moments where her public mask drops and we get a clearer sense of the “real†Joan Rivers. (Many of these moments involve Rivers’ daughter Melissa, with whom she shares a loving, but noticeably tense relationship.) Truth be told, the filmmakers seem too enthralled by their subject at times; the movie would have been more interesting had they taken a critical eye to some of Rivers’ career choices–like the notorious TV movie that dealt with her husband’s suicide in which she and Melissa played themselves–and sought out interviews with people that aren’t necessarily her biggest fans. Still, A Piece of Work is an entertaining and lively portrait of a performer whose contribution to comedy is often, and probably unfairly, overlooked.

Stonewall Uprising and 46365 open in New York this week at Film Forum and Anthology Film Archives respectively. Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work is currently playing in limited release and on video-on-demand. Click on the titles to visit the films’ official websites to learn more information.

I really enjoyed her documentary, I just saw it this past weekend. She comes across so much different than I ever imagined, she really is very talented and soooo hard working.